The Making of Bones of Yew: Part 02

🎻 Scoring the Soil: Music and Ritual in Bones of Yew

The music of Bones of Yew isn’t background—it’s backbone. From the early development stages, composer Bill Vine helped shape the sonic identity of the film, drawing deeply from folk memory, ancestral grief, and spiritual endurance. His original compositions, Per Un Autre Sol and La Vergues Astrea, form an emotional thread that weaves through the narrative, lending weight to the film’s themes of sacrifice and connection to land. Featuring vocals by renowned French counter-tenor Paulin Bündgen, and drone harmonies by Matt Kirk, the pieces balance historical lament with modern resonance. The blog explores how sound became story—through conversations, shared reference points, and an intuitive understanding between collaborators—and how music helped ground the film in something old, sacred, and still alive.

Music & Score

The Score of Bones of Yew — An Interview with Composer Jordan Hudson

When shaping the sonic world of Bones of Yew, we knew the score had to do more than just support the visuals. It had to root us in something ancient, real, and deeply human. Composer Jordan Hudson was the perfect collaborator for this challenge. With over a decade of experience as both a musician and audio engineer, Jordan brought a unique sensibility to the table: a blend of historical awareness, technical mastery, and a willingness to experiment.

In this interview, Jordan talks about his approach to scoring Bones of Yew, the symbolism woven into the music, and how AI is changing the way we compose, without replacing the soul of the work.

The Score

Hudson's sensitivity to tone and narrative comes through here: war as experienced by farmers and villagers, not knights and kings.

"The score drew heavily from instruments around the time of the Battle of Crécy. drones, reeds like accordion and bagpipes. I used a shruti box, which, though only 150 years old and an evolution of the harmonium in India, creates a very ancient-sounding drone. These instruments’ harmonic overtones naturally lean towards medieval intervals 4ths, 5ths, and octaves which shaped the tonal world. I used “pedal notes” to create beds the audience could subconsciously follow, ornamenting them with small details. My first draft was too cinematic and risked romanticising war; the director (Toby Hyder) steered it towards the peasant’s perspective, focusing on loss and sacrifice rather than heroism."

Collaborating with Muscians

Tchi-Ann’s (Violinist) contribution gave the score its melodic heart. Her vocals and violin work created an emotional throughline that helped carry the film's quieter, more reflective moments.

"Tchi-Ann played violin and sang on the score. The main theme actually came from one of her own songs we’d recorded months earlier it had a modal, ancient quality that fitted perfectly. We’ve worked together for years, so bringing her into this felt natural and her open performance added authenticity to the score."

Moments, Symbolism & Favourite Cues

"There are a few moments in the film where I felt especially proud of my contribution and to get there, I had to break a few “rules,”

particularly in harmony and instrumentation. Initially, my historically inspired palette worked beautifully, but at certain points it limited the weight I needed to bring into the scene.

One example is the moment when a messenger reads an order to the protagonist’s village, calling them to war. At that exact moment, the bagpipe enters alongside the timpani bass drum , both instruments appropriate for the period , but then a snare drum march rises underneath. While snare drums existed in the 14th century, the one I used had a 16th-century character, with steel snares, chosen for its sharper, more martial tone. That marching rhythm creates a sense of inevitability, like an axe hanging over the villagers’ heads.

they don’t know when the day will come, only that it will.

Beneath this, a sustained drone made from my usual instrumental palette supports the scene, along with another “rule-breaker”: a cello, slightly distorted, producing a deep, cinematic rumble. When the cello drops to a sixth, it gives the mind a lift while letting the heart sink — a tonal shift that puts empathy for the protagonist front and centre."

the moment when a messenger reads an order to the protagonist’s village,

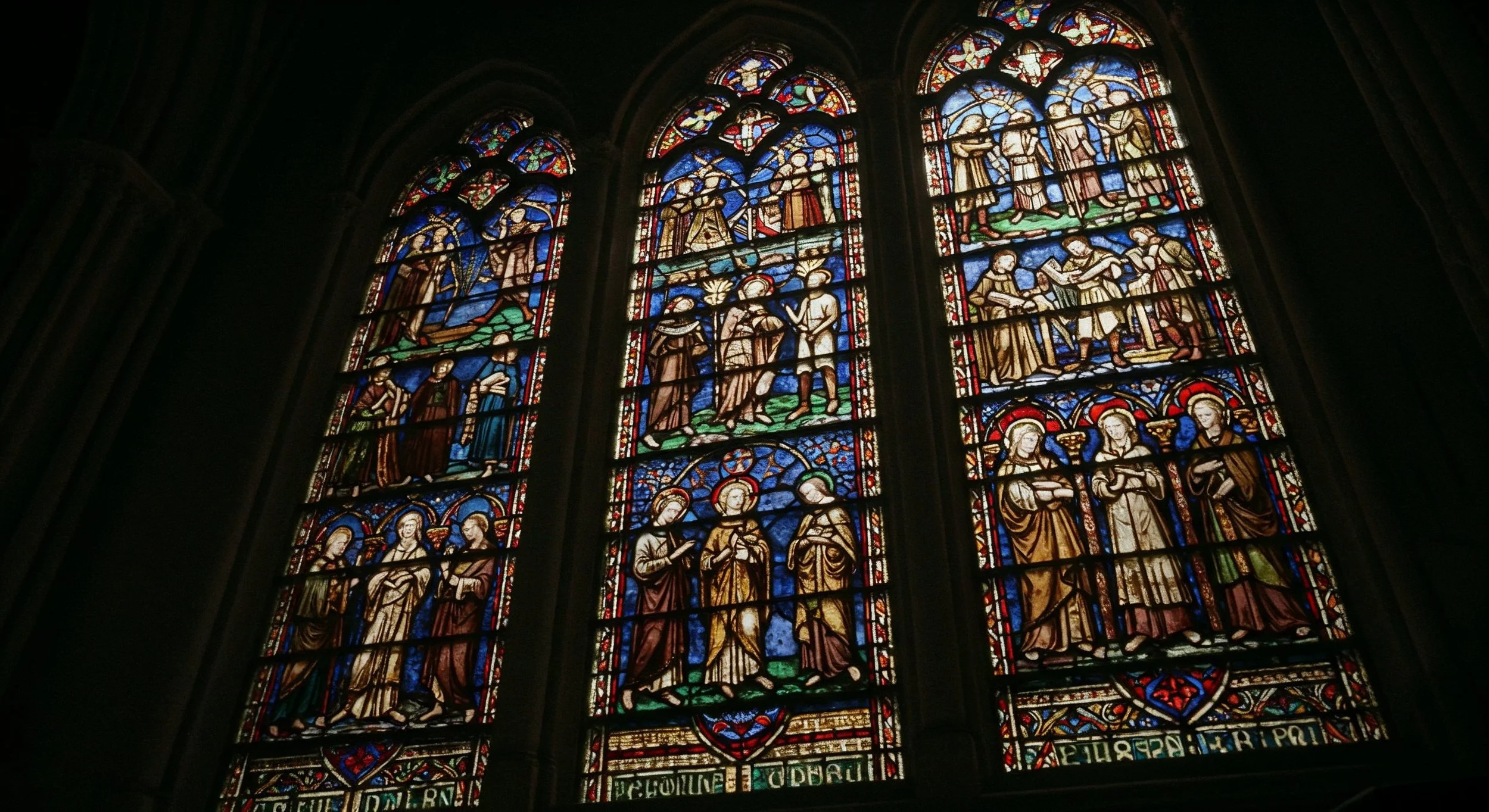

“Another moment I love is the use of Gregorian chants —

a blend of samples with my own and Tchi-Ann’s voices. These chants swell and resonate over a shot of a yew tree’s roots seeping into water, with a subtle thudding pulse underneath. The intention was to sonically mirror the tree’s life cycle , drawing water up, sending sugars down — and to convey the sense that nature, as the villagers experienced it, was a living, breathing presence in their lives."

"As for symbolism in the sound design, there are two elements worth noting. First, bells: woven into my score and also present in a pre-existing song used in the film. I scored either side of that track to integrate it fully. The bells represent the face of the Church — sometimes clear and obvious, other times hidden — reflecting its ability to disguise itself while exerting control and misusing resources under the guise of divine authority.

The second element is bird calls , specifically crows, collared doves, and wood pigeons , recorded authentically. Having grown up in southern England, these sounds are deeply nostalgic for me; they are often heard around old churches and ancient yew trees. I wanted to anchor the audience in that same landscape, reminding them that the 14th-century world was not so different from today, and that the villagers called to war then were not so different from us now.

These connections were essential for me in tying the viewer emotionally to the main character."

Listen to The score of Bones of Yew here

The Occitan Lament – A Haunting Interlude by Bill Vine & Paulin Bungen

Composer Bill Vine contributed a hauntingly beautiful track to Bones of Yew —

La Vergues Astrea, is set to the words of 16th-century poet Jehan de Nostredame. Rooted in the language and landscape of Occitanie, the music draws from a deeply personal archive of sound: field recordings, experimental drones, and his own vocal compositions later performed by French countertenor Paulin Bündgen.

“I’m not a trained classical singer … far from it … but I sketched out the melodies and handed them to Paulin, who took them somewhere astonishing. Hearing that transformation was probably my proudest moment.”

Bill recounts how he first discovered the Occitan sonnets through a residency with composer Gavin Bryars. One piece — Massat — was recorded in an ancient chapel in the Pyrenees with rich natural acoustics. That session, according to Bill, “literally brought me to tears.”

His work often blends modern and ancient textures, and for Bones of Yew, this meant composing from environmental tone and texture rather than traditional harmony. “I’ve been working with electroacoustic sound for twenty years — everything from drone notes to manipulated field recordings — so it made sense to score with those same principles.”

A notable layer of La Vergues Astrea includes a bass drone recorded by Matt Kirk in a local church, lending further weight to the piece’s earth-rooted quality.

On AI and Misconceptions in Music

Despite not using AI in the creation of his pieces, Bill is acutely aware that the project’s wider use of generative tools might lead to assumptions.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if people thought the music was AI-generated , purely because they know the film is. That’s part of what fascinates me: how people’s assumptions shape their perception.”

Bill sees this as both a challenge and an opportunity. Rather than reject AI outright, he believes we should guide its use responsibly — especially in art.

“It’s still early days. We need more people using AI in thoughtful, creative ways. Tools are only dangerous if they’re misused.”

For Bill, AI isn’t about shortcuts; it’s about pushing creative boundaries, provoking new ideas, and inviting reinterpretation. That’s why, even though he didn’t initially write the pieces for Bones of Yew, he was happy to see them repurposed into a filmic context.

“I’m not precious about the music. It’s lovely when someone uses it in a way I hadn’t imagined , it gives it a new and different life.”

hear it live!

Bill continues to explore Occitan sonnets, working with Paulin Bündgen on an expanding body of work. In fact, Paulin will perform a selection of these pieces live in Norwich Sunday 21st of september — a testament to how far this music has travelled, both geographically and emotionally.

Link to event here

“To have him want to keep singing these pieces — and to come over from France to perform them live — I’m incredibly proud and humbled.”

The Making of Bones of Yew: part 01

As AI filmmaking continues to explode creatively and technically, one thing remains clear: what separates good from exceptional work is the data you feed it. and When we say “You” we mean YOU! the film maker

Why sourced Input Data Defines the Best in AI Filmmaking

As AI filmmaking continues to explode creatively and technically, one thing remains clear: what separates good from exceptional work is the data you feed it. and When we say “You” we mean YOU! the film maker

At XOlink, we believe the future of AI-assisted storytelling hinges on attention to input. The most advanced models in the world can only work with what they have, so what can you build on top?

if you give them noise, they’ll give you noise back… But give them something rich, textured, real , and suddenly, you’re making cinema.

That’s the philosophy behind Bones of Yew. Yes, it’s an AI film, but it’s also a deeply physical one.

Getting Into the Field

We went out into the ancient yew forests of England and documented them ourselves. These trees, twisted, towering, some thousands of years old. formed the symbolic and aesthetic heart of the project.

We built a dataset of their natural forms:

From this, we built a high-resolution dataset of their natural forms: chaotic, beautiful, weathered by time. Using this dataset, we trained custom LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) models, essentially creating a new pigment to paint with, one rooted in real bark, branch, and canopy.

The result? Subtle, but powerful.

Our majestic tree shots were all informed by what we sourced

at the film’s end we used this technique to push the creation in new ways, a strange and striking deer appears. its form subtly shaped by the same yew data. Its silhouette and antlers aren’t generic fantasy; they carry the ghostly, twisted geometry of the yew itself. In that moment, AI doesn’t invent. It reflects. And what it reflects is ancient, wild, and deeply grounded in place.

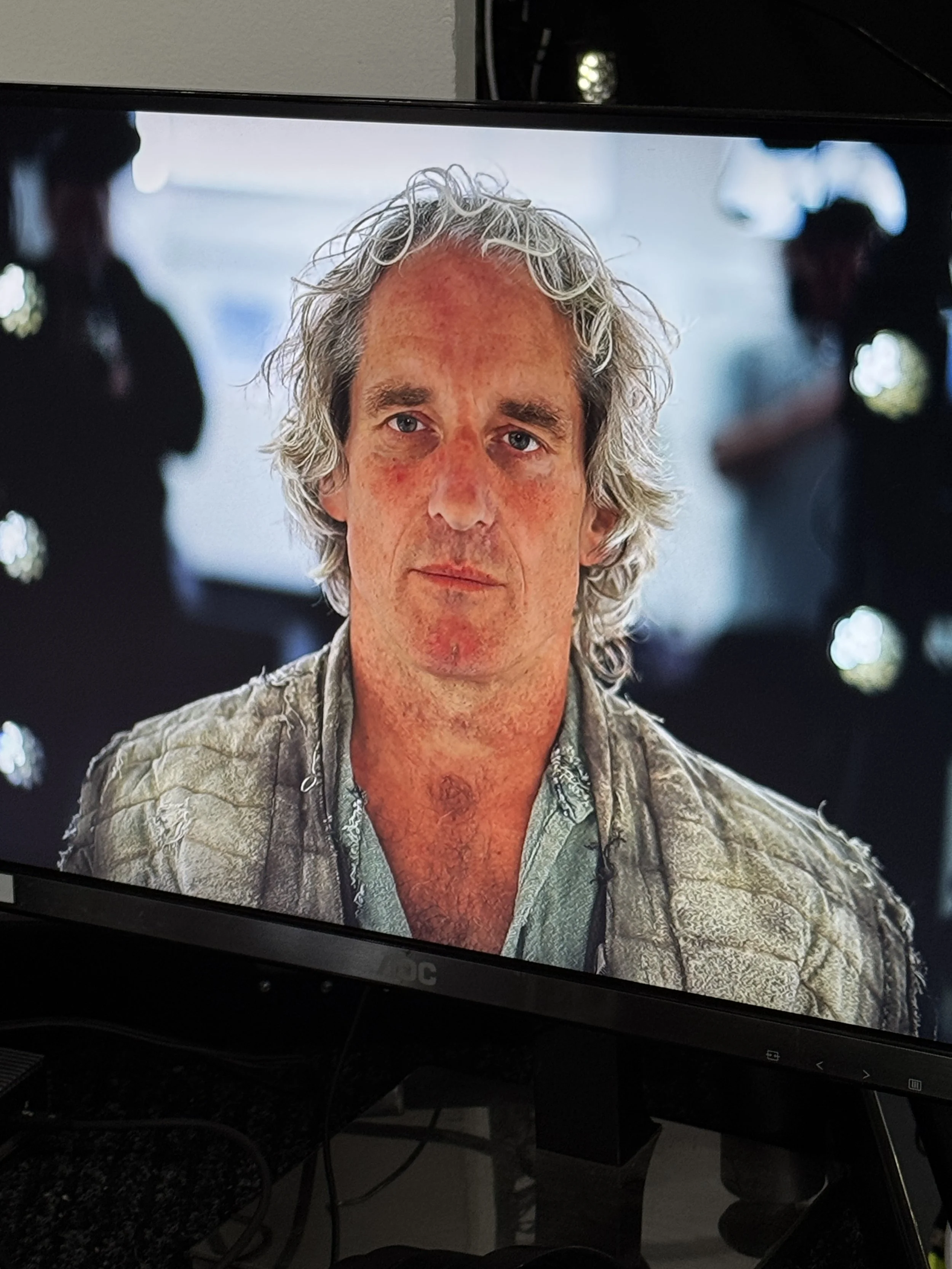

recreating Matt Lewis: Precision at Scale with Visualskies

To bring our human performance into the same world of authenticity, we partnered with the incredible team at Visualskies, who provided access to their 3D human scanning rig, a cutting-edge photogrammetry system designed for high-speed, high-fidelity capture.

In a single session, we were able to capture Matt Lewis in full,

generating volumetric data of his posture, face, and 3 different costumes, all with millimetre-level accuracy. This rig allowed us to scan quickly and at scale, making it possible to work within the demands of production without compromising on quality.

This kind of mass-capture precision meant that even after passing through the layers of AI processing, Matt’s physicality and nuance remained intact , his presence anchoring the film emotionally, even when visually transformed.

What’s more, by training a LoRA on this base data, we were able to age him across the film with realism and continuity , subtly shifting his features, posture, and presence as time passed in the story, while preserving the core of his scanned likeness. The result is an AI-driven transformation that still feels deeply human.

We’ll be exploring Matt Lewis’s performance in greater depth in a later episode of the making of— looking at how his physical work and our data pipeline combined to shape the emotional arc of the film.

Motion Matters - Fletched, Drawn, and Trained

NOCK ! DRAW! LOOSE!

We partnered with longbow experts from the Longbow Heritage Society to capture archery in motion, not from stock clips or simulations, but from real-world practice. Real archers, real bows, real weather. The way the wood bends under tension, the draw of the string, the stance, breath, and shifting weight of the body these became the visual and physical grammar we taught to the AI.

This wasn’t just technical R&D. It was a commitment to truth in form.

We are all aware of the challenges AI has with hands…. now add Archery into the mix!

current foundation models struggle to depict the precise technique of longbow archery. From the posture of the archer to the nuanced tension in the bow hand, generic AI tools often default to cinematic cliché or guesswork. That’s where our hands-on method came in. The intent to be trained on specific, correct motion ,drawing from the centuries-old discipline of traditional English longbow use, not vague modern approximations.

At the centre of this work was Carol, from Carol Archery, our incredible weapons master. She not only coached our team and demonstrated historically accurate technique, she also supplied the actual bows used on set and even fletched a bespoke arrow for us, which became a reference object for both visual capture and AI training. She’s spent a lifetime immersed in the world of longbows, and with a wry smile told us:

“Even with all the training in the world, the archers and historians I know will still say it’s wrong.”

Book a lesson with carol at :Carol Archery she’s awesome!

That arrow appears in the final film, not just as a prop, but as essential data ,a piece of handcrafted heritage woven into the generative process.

courtesy of Carol’s fletching skills

This process helped create something few AI films attempt: an embodied realism, where the movement of the archer feels not just convincing but lived-in… because it was.

This film was awesome to make. we learned Archery is very fun. It’s physical, ancient, and unexpectedly cinematic when approached with care. But more than anything, this project showed us that we’re only just scratching the surface of what AI filmmaking can become when grounded in real-world craft and culture.

This is just the cusp of our discovery , and we’re drawing the bowstring back for more.

THE Making of Bones of Yew Part 02 to follow …

Coral Cortex

It all begins with an idea.

At XOlink, we’re always exploring the space between imagination and reality—and Coral Cortex is a reflection of that ethos.

The concept emerged from conversations with Tokyo based avant garde hairstylist Nari, whose lifelong connection to the ocean forms the emotional core of this work. Raised in a quiet seaside town in Japan, Nari spent his childhood immersed in the water studying shells and fish, swimming for hours, and seeing the ocean not just as nature, but as home. Years later, a visit to Kerama in Okinawa, one of the clearest and most pristine marine regions in Japan, sparked a deep fascination with coral. Its textures, movement, and living geometry made a lasting impression.

“As a hair stylist, I always wondered if coral and hair could come together,” Nari explains.

“And with Toby and XOlink, we were able to make it happen.”

The result is Coral Cortex, a digital series that explores the possibilities of merging human beauty with natural marine life. Using generative tools like Luma AI and Kling 2.0, we created flowing visuals of hair transforming into coral a seamless organic fusion that feels both surreal and grounded. Kling’s ability to generate hyper-realistic, fluid motion allowed us to depict underwater movement with astonishing grace: strands bloom like soft coral, swaying gently as if caught in a current. The play of sunlight filtering through the virtual water adds a sense of emotional weight and otherworldly calm.

Unlike traditional shoots that rely on physical sets, costumes, lighting, and travel, this collaboration took place entirely in the digital realm. The result? A lower carbon footprint, greater creative freedom, and the ability to experiment with visual ideas that would be nearly impossible in real life. We believe this is a powerful example of how AI can be used not just as a tool, but as a partner in the creative process, offering new ways of seeing, dreaming, and designing.

To complete the piece, we worked with ambient music artist Satellite (@solesatellite), whose haunting, spacious compositions evoke the feeling of submersion. The score built around a sense of breath, tide, and quiet reverence deepens the immersion and enhances the dreamlike atmosphere of the series.

Coral Cortex is more than a single project; it is the beginning of a broader conversation between disciplines. It asks what it means to create in the age of machine vision and reminds us that our memories of nature, childhood, and beauty can all be transformed into something new through collaboration.

Explore the ongoing Coral Cortex series now on XOlink,

nari, and satellite.