The Making of Bones of Yew: Part 02

🎻 Scoring the Soil: Music and Ritual in Bones of Yew

The music of Bones of Yew isn’t background—it’s backbone. From the early development stages, composer Bill Vine helped shape the sonic identity of the film, drawing deeply from folk memory, ancestral grief, and spiritual endurance. His original compositions, Per Un Autre Sol and La Vergues Astrea, form an emotional thread that weaves through the narrative, lending weight to the film’s themes of sacrifice and connection to land. Featuring vocals by renowned French counter-tenor Paulin Bündgen, and drone harmonies by Matt Kirk, the pieces balance historical lament with modern resonance. The blog explores how sound became story—through conversations, shared reference points, and an intuitive understanding between collaborators—and how music helped ground the film in something old, sacred, and still alive.

Music & Score

The Score of Bones of Yew — An Interview with Composer Jordan Hudson

When shaping the sonic world of Bones of Yew, we knew the score had to do more than just support the visuals. It had to root us in something ancient, real, and deeply human. Composer Jordan Hudson was the perfect collaborator for this challenge. With over a decade of experience as both a musician and audio engineer, Jordan brought a unique sensibility to the table: a blend of historical awareness, technical mastery, and a willingness to experiment.

In this interview, Jordan talks about his approach to scoring Bones of Yew, the symbolism woven into the music, and how AI is changing the way we compose, without replacing the soul of the work.

The Score

Hudson's sensitivity to tone and narrative comes through here: war as experienced by farmers and villagers, not knights and kings.

"The score drew heavily from instruments around the time of the Battle of Crécy. drones, reeds like accordion and bagpipes. I used a shruti box, which, though only 150 years old and an evolution of the harmonium in India, creates a very ancient-sounding drone. These instruments’ harmonic overtones naturally lean towards medieval intervals 4ths, 5ths, and octaves which shaped the tonal world. I used “pedal notes” to create beds the audience could subconsciously follow, ornamenting them with small details. My first draft was too cinematic and risked romanticising war; the director (Toby Hyder) steered it towards the peasant’s perspective, focusing on loss and sacrifice rather than heroism."

Collaborating with Muscians

Tchi-Ann’s (Violinist) contribution gave the score its melodic heart. Her vocals and violin work created an emotional throughline that helped carry the film's quieter, more reflective moments.

"Tchi-Ann played violin and sang on the score. The main theme actually came from one of her own songs we’d recorded months earlier it had a modal, ancient quality that fitted perfectly. We’ve worked together for years, so bringing her into this felt natural and her open performance added authenticity to the score."

Moments, Symbolism & Favourite Cues

"There are a few moments in the film where I felt especially proud of my contribution and to get there, I had to break a few “rules,”

particularly in harmony and instrumentation. Initially, my historically inspired palette worked beautifully, but at certain points it limited the weight I needed to bring into the scene.

One example is the moment when a messenger reads an order to the protagonist’s village, calling them to war. At that exact moment, the bagpipe enters alongside the timpani bass drum , both instruments appropriate for the period , but then a snare drum march rises underneath. While snare drums existed in the 14th century, the one I used had a 16th-century character, with steel snares, chosen for its sharper, more martial tone. That marching rhythm creates a sense of inevitability, like an axe hanging over the villagers’ heads.

they don’t know when the day will come, only that it will.

Beneath this, a sustained drone made from my usual instrumental palette supports the scene, along with another “rule-breaker”: a cello, slightly distorted, producing a deep, cinematic rumble. When the cello drops to a sixth, it gives the mind a lift while letting the heart sink — a tonal shift that puts empathy for the protagonist front and centre."

the moment when a messenger reads an order to the protagonist’s village,

“Another moment I love is the use of Gregorian chants —

a blend of samples with my own and Tchi-Ann’s voices. These chants swell and resonate over a shot of a yew tree’s roots seeping into water, with a subtle thudding pulse underneath. The intention was to sonically mirror the tree’s life cycle , drawing water up, sending sugars down — and to convey the sense that nature, as the villagers experienced it, was a living, breathing presence in their lives."

"As for symbolism in the sound design, there are two elements worth noting. First, bells: woven into my score and also present in a pre-existing song used in the film. I scored either side of that track to integrate it fully. The bells represent the face of the Church — sometimes clear and obvious, other times hidden — reflecting its ability to disguise itself while exerting control and misusing resources under the guise of divine authority.

The second element is bird calls , specifically crows, collared doves, and wood pigeons , recorded authentically. Having grown up in southern England, these sounds are deeply nostalgic for me; they are often heard around old churches and ancient yew trees. I wanted to anchor the audience in that same landscape, reminding them that the 14th-century world was not so different from today, and that the villagers called to war then were not so different from us now.

These connections were essential for me in tying the viewer emotionally to the main character."

Listen to The score of Bones of Yew here

The Occitan Lament – A Haunting Interlude by Bill Vine & Paulin Bungen

Composer Bill Vine contributed a hauntingly beautiful track to Bones of Yew —

La Vergues Astrea, is set to the words of 16th-century poet Jehan de Nostredame. Rooted in the language and landscape of Occitanie, the music draws from a deeply personal archive of sound: field recordings, experimental drones, and his own vocal compositions later performed by French countertenor Paulin Bündgen.

“I’m not a trained classical singer … far from it … but I sketched out the melodies and handed them to Paulin, who took them somewhere astonishing. Hearing that transformation was probably my proudest moment.”

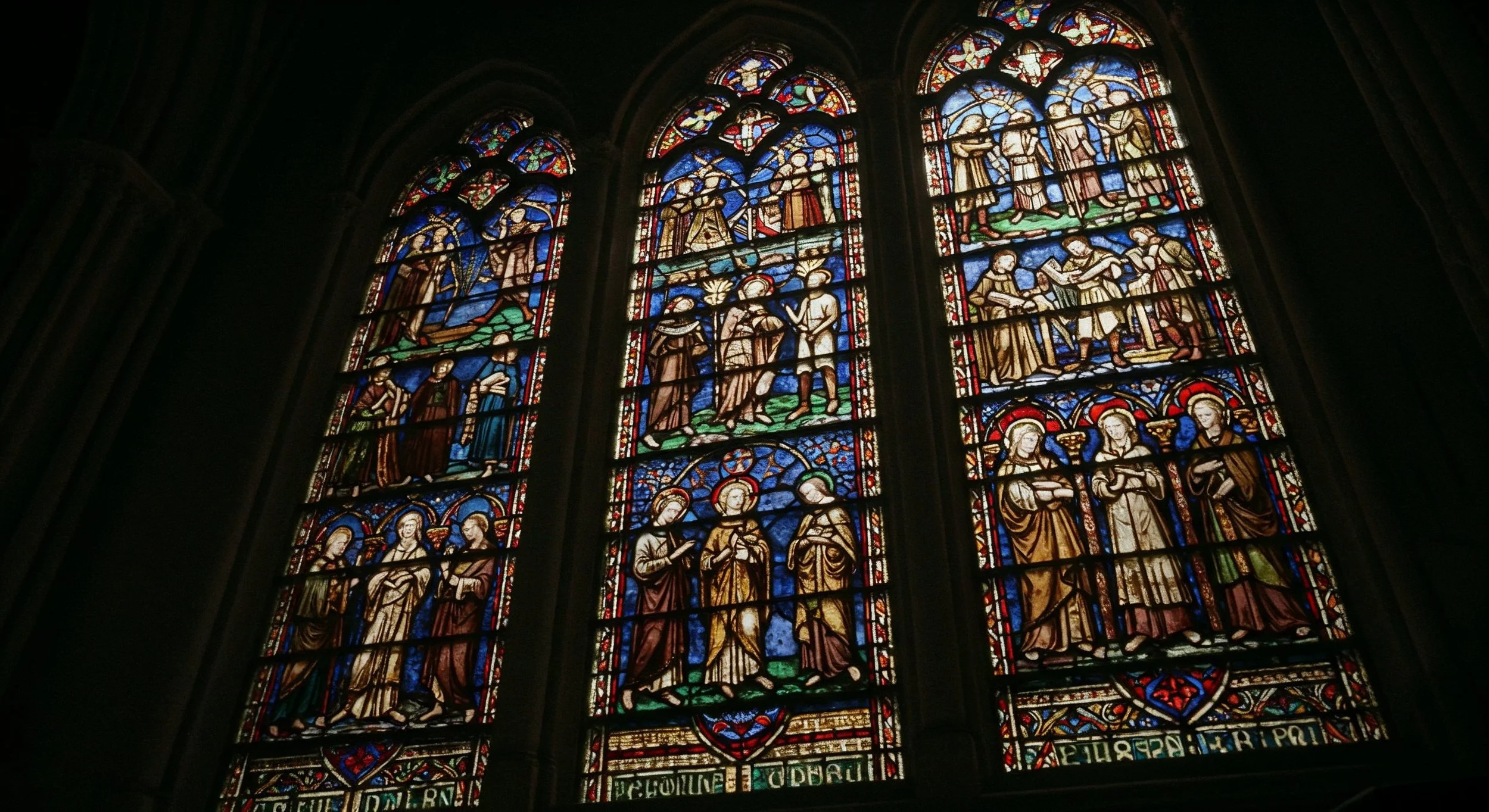

Bill recounts how he first discovered the Occitan sonnets through a residency with composer Gavin Bryars. One piece — Massat — was recorded in an ancient chapel in the Pyrenees with rich natural acoustics. That session, according to Bill, “literally brought me to tears.”

His work often blends modern and ancient textures, and for Bones of Yew, this meant composing from environmental tone and texture rather than traditional harmony. “I’ve been working with electroacoustic sound for twenty years — everything from drone notes to manipulated field recordings — so it made sense to score with those same principles.”

A notable layer of La Vergues Astrea includes a bass drone recorded by Matt Kirk in a local church, lending further weight to the piece’s earth-rooted quality.

On AI and Misconceptions in Music

Despite not using AI in the creation of his pieces, Bill is acutely aware that the project’s wider use of generative tools might lead to assumptions.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if people thought the music was AI-generated , purely because they know the film is. That’s part of what fascinates me: how people’s assumptions shape their perception.”

Bill sees this as both a challenge and an opportunity. Rather than reject AI outright, he believes we should guide its use responsibly — especially in art.

“It’s still early days. We need more people using AI in thoughtful, creative ways. Tools are only dangerous if they’re misused.”

For Bill, AI isn’t about shortcuts; it’s about pushing creative boundaries, provoking new ideas, and inviting reinterpretation. That’s why, even though he didn’t initially write the pieces for Bones of Yew, he was happy to see them repurposed into a filmic context.

“I’m not precious about the music. It’s lovely when someone uses it in a way I hadn’t imagined , it gives it a new and different life.”

hear it live!

Bill continues to explore Occitan sonnets, working with Paulin Bündgen on an expanding body of work. In fact, Paulin will perform a selection of these pieces live in Norwich Sunday 21st of september — a testament to how far this music has travelled, both geographically and emotionally.

Link to event here

“To have him want to keep singing these pieces — and to come over from France to perform them live — I’m incredibly proud and humbled.”